Standard preparation by drying

The standard preparation of beetles is almost exclusively by desiccation. This preserves them perfectly. In the context of drying preparation, the following basic operations are carried out:

- preparing of the specimen before preparation (if the specimen is dried before preparation, it has to be softened again);

- cleaning of the whole body (the specimen is cleaned of dirt and, if necessary, grease);

- straightening (flattening of the twisted body);

- adjustment of the legs and antennae according to the method of preparation;

- fixing the specimen;

- drying the specimen;

- provision of a locality label.

We will describe each of these steps in more detail below.

1. Preparing of the specimen before preparation

As mentioned in previous chapters, specimens are stored after collection either in a supple state, in ethyl acetate vapour or in a freezer box, or as dried specimens.

If we have the specimenina supple state, we can proceed to the next step of preparation. In this case, we prepare the beetles on the 2nd or 3rd day after they are killed, when they are most supple. Immediately after killing they may still be "in spasm" and the preparation could be difficult. However, the beetles can be kept supple in acetate vapour for up to 1 year. Beware, however, of some coloured individuals, which may lose their colour after only a few hours (see chapter Basic collection methods and tools). If specimens are kept in ethyl acetate vapour for a longer period of time, the concentration in the vial must be maintained, i.e. usually a few drops of acetate should be added every few days (depending on how well the vial seals). If we forget to do this, it is often necessary to soften the specimens in a dehumidifier before the actual preparation, as in the case of completely dried specimens. The dehumidification time is somewhat shorter for partially dried specimens - we can usually prepare such specimens after 10 to 12 hours.

Frozen specimens

Frozen specimens are removed from the freezer and allowed to thaw at room temperature for about 60 minutes. After this time, they are supple and ready for the next step of preparation.

Dried specimens

Dried specimens must first be softened. This is done in a container we call a dehumidifier. This can be any lower dish that can be covered with a lid or some sort of cover. Petri dishes are very suitable for this purpose. I place about 4 layers of paper kitchen towels in the bottom of the bowl, cut to the size of the bowl I am using. Using an eyedropper or a spatula, I gently dampen the layers of dish towels and sprinkle a few drops of 10% vinegar or Ajatin disinfectant - this is to protect against possible mould growth. I carefully place the collection in the dehumidifier thus prepared, close the bowl and let the bugs slowly dehumidify. Allow for the fact that at room temperature the dehumidification process can take about 24 hours. After about 10-15 hours of humidification, the beetles can be gently handled and a little water can be added. After 24 to 36 hours, the beetles are sufficiently dehumidified and ready for further preparation. If we have different types of specimens in the dehumidifier, it is important to note that delicate specimens will be dehumidified much sooner than large or more chitized species. Therefore, it is advisable to prepare fine specimens preferentially to avoid the risk of over-wetting.

A quick way to dehumidify dried specimens is to immerse them in Barber's solution for 30 minutes. Barber's solution is a mixture with the following composition:

- 1 000 ml of 95% ethanol,

- 1 000 ml of distilled water,

- 375 ml of ethyl acetate (ethyl acetate),

- 125 ml of benzene.

After approximately 30 minutes in Barber's solution, the beetles are dehumidified so that they can be prepared.

Problematic specimens

Sometimes it happens that even after a well performed dehumidification some specimens are still unable to perform the preparation. This usually happens in specimens that have come into our collection from elsewhere and have been "badly killed" (e.g. by using an inappropriate killing agent) or in some heavily sclerotized specimens. The susceptible species are often members of the family Curculionidae. In such cases, it is necessary to dehumidify the specimen in a somewhat coarser way, but even so, we never know whether the result will be a well-palatable specimen.

We can try to moisten such "problem specimens" by placing the specimen in boiling water. In doing so, we take care that the specimen is not knocked against the sides of the container. After approximately 30-60 minutes of boiling, remove the specimen and see if it has "softened" a little. If not, try adding a little acetic acid to the container and continue cooking for another 30-60 minutes. If this does not help, try to dehydrate the specimen with carbon dioxide pressure. This is done as follows.

Take a wide-mouth bottle with a tight-fitting cap. Pour some vinegar into the bottle and fill it with soda water up to the bottom of the neck. As quickly as possible, insert the dehydrated specimens and cap the bottle. Specimens are usually dehumidified after 15 to 60 minutes - depending on their size and degree of sclerotization. Do not leave the specimens in the solution for more than 90 minutes as there is a risk of overhydration. The moistening effect is very strong and the method is particularly suitable for larger and more heavily sclerotized individuals. If even this method of moistening does not help, we must accept that the specimen will not be well prepared.

2. Cleaning the entire body of the specimen

Routine cleaning of most specimens consists of gently cleaning them with a fine brush, and the size of the brush should be appropriate to the specimen being cleaned. Use a smaller and finer brush on delicate and smaller specimens (e.g., size 0 to 2) compared to larger and more sclerotized specimens (e.g., size 4 to 12). In the case of heavier soiling, dip the brush in a soapy water solution.

For individuals that are oily, use one of the solvents such as ethyl acetate, benzene, ether, or alcohol to degrease. Cleaning off the grease may have the positive effect of subtly brightening the colour of the specimen in some individuals.

If we get hold of specimens that need to be cleaned of mould, we use chloroform or ethyl acetate. However, cleaning off mould is always problematic and with uncertain results.

The next steps of the preparation are carried out on the preparation plate.

3. Leveling the specimen

The first step in the preparation plate is the basic alignment of the specimen. This is done using a reasonably sized brush or a preparation needle. The prepared specimen is flattened so that it is not bent or otherwise twisted.

4. Adjustment of legs and antennae

Perform the basic preparation of the legs and antennae according to the chosen method of preparation by drying: impaling on an entomological pin or sticking on a label. When preparing the specimen, place the specimen on the preparation plate, ventral side up.

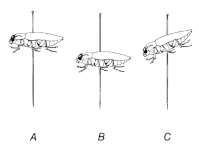

In the case of the 'impaling on entomological pin' method, align the limbs so that they face as little away from the body as possible - the front legs facing forwards, the middle and hind legs facing backwards, not sideways. Align the antennae along the body so that they point backwards.

In the 'stick-on' method, align the limbs so that they are as far away from the body as possible. If the antennae are short, they can be aligned so that they point forward. Long antennae are aligned along the body. Straighten also the scapulae towards the front or, in the case of predatory specimens, open the antennae. When working, hold the specimen with a cover glass to fix the specimen and compare the limbs and other appendages with a preparation needle or brush.

5. Fixing the specimen

As mentioned in the previous section, we use two basic methods in this method of preparation:

- impaling on an entomological pin

- sticking on a label

There is no regulation or standard that tells us when to use either of these two methods. The general rule is that we impale large specimens and stick small specimens. However, the line between large and small specimens is for each individual to determine. At present, the prevailing view is that sticking on the label takes priority. Aesthetic considerations prevail, with many entomologists arguing that piercing the trunk will actually damage the specimen. From a scientific point of view, this argument does not hold up, because the beetle's body integument is symmetrical and we are still left with the other, undamaged scutellum for scientific study. I have personally encountered impaled specimens of about 5 mm in size in foreign museums. For those of you who are just starting out in entomology, here are the limits I have set for myself:

- i apply entomological pinning to specimens that are larger than 15 mm;

the exception is the Staphylinidae, where I also stick large specimens on the tag; - specimens up to 15 mm are then labelled;

in addition, for specimens smaller than 3 mm, I sometimes apply the method of creating a microscopic slide by enclosing it in an air chamber (see below).

Pinning on an entomological pin

Depending on the size and skeletal rigidity of the specimen to be prepared, choose an entomological pin of the appropriate size. The vast majority of Czech beetles can be impaled on size 2 or 3 pins. Size 1 pins should exceptionally be used for thin specimens or for specimens that have a very delicate skeleton (soft trunks). On the other hand, we use size 4 pins on the largest specimens that have very hard scutes. We usually impale specimens larger than 35 mm with them.

Depending on the size and skeletal rigidity of the specimen to be prepared, choose an entomological pin of the appropriate size. The vast majority of Czech beetles can be impaled on size 2 or 3 pins. Size 1 pins should exceptionally be used for thin specimens or for specimens that have a very delicate skeleton (soft trunks). On the other hand, we use size 4 pins on the largest specimens that have very hard scutes. We usually impale specimens larger than 35 mm with them.

The specimen aligned according to 3 and 4 is placed on the preparation plate with the scruff upwards and the pin is inserted perpendicularly in the middle of the first third of the right scruff (see picture). At the same time, fix the specimen with your hand to the pad. We really make sure that the pin is perpendicular to the body axis, because the final appearance of the prepared specimen depends on the correct impalement. When pricking, we are careful not to squeeze the hip of the leg out of its hollow. Insert the pin into the body of the specimen so that it protrudes at least 1 cm above the body.

Now take the prepared specimen with a pair of hard tweezers and insert the head of the pin into the 10 mm hole. With the tweezers, apply pressure to the ventral side and move the impaled specimen along the pin so that a space of 10 mm remains between the end of the pin with the head and the prepared specimen. This gives us a height adjustment of the prepared specimen. The pin with the specimen is now inserted into the preparation plate so that the specimen touches the ventral side of the plate. Be careful not to move the specimen along the pin during this manipulation, as we would disturb the height adjustment of the specimen and would have to correct it using the elevation pin.

We will now make the final alignment of the limbs, antennae and maculae. In doing so, we help ourselves with the fixing pins, which we use to "pin" the specimen. We align the limbs under the body so that only the joints between the thighs and shins protrude on the middle and hind legs, and the front legs are folded next to the head and point forward. Align the antennae along the body towards the rear. Macaws point forward. The legs of the prepared specimen may be slightly open.

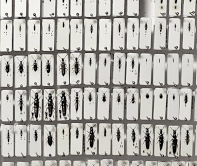

The described method of preparation by impaling is suitable for scientific collections, where it is preferred to protect the specimen from damage and emphasis is placed on not taking up so much space in the collection. If you are building a collection primarily for presentation, then such preparation is more concerned with making the specimen as visible as possible. This means that the limbs are not placed so much under the body, but rather aligned along the body.

We place a collection information card with the specimen prepared in this way - the basis for a future locality label. Sometimes a printed locality label is attached directly to the specimen at this stage.

Sticking on the label

Check the specimen to ensure that the limbs and other appendages are aligned according to point 4. Turn the specimen upside down and again check the symmetry of the alignment of the limbs and all appendages. Remove any defects with a fine brush or tweezers while fixing the slide with a coverslip preparation. Adjust the legs so that they are clearly visible on the sides of the body and give a natural impression - the beetle must look as if it is climbing.

Check the specimen to ensure that the limbs and other appendages are aligned according to point 4. Turn the specimen upside down and again check the symmetry of the alignment of the limbs and all appendages. Remove any defects with a fine brush or tweezers while fixing the slide with a coverslip preparation. Adjust the legs so that they are clearly visible on the sides of the body and give a natural impression - the beetle must look as if it is climbing.

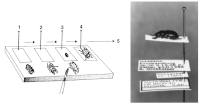

Now select a sticker of the appropriate size. The preparation must fit on the label, no part of the body should extend over the edge of the label. On the other hand, the label should not be too large, so that the preparation "disappears" on it. Apply a drop of glue to the label - use, for example, an entomological pin with the head cut off. Apply the glue so that it is positioned between the hips of the first and second pair of legs (see picture). Then move the slide onto the glue plate.

If there is any displacement of the legs by moving the slide onto the glue plate, we can carefully make a correction, holding the slide with a cover slip to fix the specimen. The final correction is then made after the glue has dried sufficiently (10 - 20 minutes).

Finally, pierce the label with a pin (I have the best experience with size 3 pins, which hold the adhesive label firmly enough) and adjust the height of the prepared specimen to 25 mm using a height adjuster. Move the finished specimen to the place designated for final drying.

Attach a collection information slip to the prepared specimen - the basis for a future locality label. Sometimes a printed locality label is attached directly to the specimen at this stage.

After gaining some experience with the preparation, we perform the specimen mounting operation, usually for several specimens at the same time.

6. Drying of the specimen

After completion of step 5, the drying stage of the slide begins. The length of drying depends on the size of the specimen and the climatic conditions under which the drying takes place.

At an average humidity of 50% and a temperature of 22°C (normal apartment block) I leave the glued specimens to dry for at least 1 week, the impaled specimens dry for about 1 month. These are times that are more than sufficient for a good drying of the specimen. These times would be sufficient for drying even in worse conditions, e.g. at 50 - 60% humidity.

The preparations are usually dried in a place where air flow is ensured. In winter this may be near a heater, for example. At the same time, however, we should also ensure that the drying area is free of dust. These seemingly contradictory requirements can be met, for example, by placing the pads with the dried preparations in a larger cardboard box, which is occasionally 'aired out'.

When the drying phase is complete, carefully remove the fixation pins from the impaled specimens.

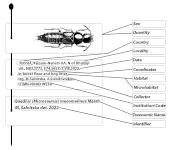

7. Location label measures

Once the drying phase is complete, all that remains is to label the specimen with the locality label, the date of finding and who found the specimen. This is a very important part of the preparation, at least as important as the quality of the preparation itself.

The locality label is placed under the specimen being prepared. For labelled specimens, it is placed at a height of 21 mm from the tip of the pin. Beetles impaled on a pin usually have a greater thickness and the locality label is placed a few mm below the impaled specimen - if we have a pin that has other positions (17 and 13 mm), we place the label at the next lower position (usually 17 mm).

The size of the label should match the size of the sticker on the glued specimen, or should not overhang the sticker too much. This is relatively easy to comply with for larger sticker labels. For smaller labels, we try to place the necessary information in as small an area as possible so that the locality label overlaps the sticker label only to the extent necessary. Although there is no standard for the size of location labels, the maximum recommended size in the literature is 7 x 18 mm.

For more detailed rules on the writing of locality labels, see the page "Preparation tools".

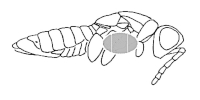

Special features of the preparation of the genus Meloe

Preparation of the genus Meloe is a little more complicated, because after point 2 of the above preparation procedure we have to include point 2A, which consists in cutting the posterior, removing its contents, then cleaning and stuffing.

The body of Meloe contains a large amount of fat, which would prevent the preparation from drying out during conventional preparation - it would rather cause the preparation to rot. In addition, it would also destroy the rump, which is covered only by a very thin body covering. For these reasons, it is necessary to literally "eviscerate" and stuff the Meloe.

Transfer the mayfly killed with acetic ether to a preparation mat, ventral (ventral) side up. Cut the rump lengthwise with a pair of fine scissors or a scalpel, down to the sternal segments. Using hard tweezers, remove the oily contents of the buttocks and insert a cotton swab into the buttocks instead. The specimen is then immersed in petrol to degrease the remaining fatty tissue. If necessary, change the petrol several times. When the excrement is sufficiently degreased, the swab is removed from the buttocks and after the petrol has evaporated (about 3-5 minutes), the buttock cavity is carefully filled with dry cotton wool until it is a natural shape. Insert the padding into the buttocks in small pieces, spreading the cotton wool with gentle pressure until the natural shape of the buttocks is achieved. Finally, use gentle pressure with your fingers to squeeze the slit hole so that the cotton wool does not protrude.

After this intermediate step, we continue the preparation with the following points: 3 to 7.

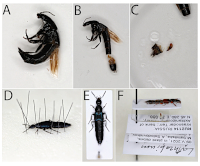

Preparation of the copulatory organs

This is used to determine certain species in which their uniformity makes it difficult to classify them as a species or subspecies. In these cases, we prepare the male copulatory organ, which is surrounded by a special chitinous sheath with characteristic tips and an internal sac. The female genitalia are also prepared, but their anatomy is not nearly as well documented as that of the male organs.

Preparation of the male copulatory organ is relatively easy in most specimens after some training. Specimens undergoing copulatory organ preparation must be well dehydrated.

In larger species, we proceed by inserting a slightly curved preparation needle between the last sternite and the tergite of the rump and gently pushing the entire copulatory organ out.

In small species, we perform the preparation under a microscope and instead of the preparation needle we use the smallest entomological pins (000) or minute needles inserted into thin handles.

In some cases, however, it is necessary to tear off the last articles of the hindgut (8th-10th abdominal segment). The removed copulatory organ is usually boiled in a 10% KOH or NaOH solution, which dissolves the blanched parts and leaves a clean aedeagus: this, after washing with distilled water and drying, is usually glued on a label to the main preparation. Alternatively, it can be stored in glycerol in a sealed plastic tube (0.5 ml eppendorf), which can be pinned to the main slide or made into a separate microscopic slide.

The procedure for preparation of small specimens, published in the West Bohemian Entomological Journal:

Milan Boukal & Karel Rébl: Clambus gibbulus - first record for the Czech Republic (Coleoptera: Clambidae), Západočeské entomologické listy (2011), 2: 37-40

|

Preparation and dissection of male genitalia is very difficult and laborious due to the small size of beetles of the genus Clambus and requires some experience, as careless manipulation often leads to the disintegration of the very fragile imago. We have found it useful to gently grasp the beetle in two fingers, ventral side up, and detach (tear off) the entire abdomen with hard watchmaker's tweezers. The whole procedure must be done under a binocular magnifying glass. The use of a thin pin to separate the rump is not advisable, especially not on a mat, as this often results in the scutellum and usually the head and shield falling off. For removal of the male genitalia, it is preferable to place the entire posterior in a small drop of glycerine, preferably on matrix glass (i.e. glass with a treated glass surface, e.g. by sandblasting, etching, etc.). Matrix glass is used in preparations using a binocular loupe or microscope because it prevents the small pressed-on parts from rolling through better than smooth glass. With one entomological pin, press the butt of the pin in a drop of glycerine onto the matrix glass and with the other carefully break the blanched tergites. Performing this operation on a 'dry' mat, i.e. without glycerine, could result in the entire butt bouncing off and, due to its tiny size, being lost. The use of a small drop of water is not advisable because, unlike glycerine, it dries out very quickly, especially if we have a strong heat-emitting light near the microscope. Carefully clean the prepared aedeagus with entomological pins and place a drop of the fully water-soluble artificial resin di-methyl-hydatoin-formaldehyde [DMHF, (C6H10N2O3)X] directly next to the beetle on the label. Rotate the aedeagus to a suitable position for determination and allow the resin to set for several minutes to hours. No illumination of the aedeagus is then necessary. For invertebrates, the use of DMHF was first proposed by STEEDMAN (1958) and after him the methodology was modified with respect to the specifics of beetles of different families, e.g. by ANGUS (1969), BAMEUL (1990) and others. Compared to many other artificial resins, DMHF has the advantage that the embedded objects do not have to be passed through alcohol and xylene series or use special solvents (isopropanol, xylene, etc.). It is also not necessary to wash the small aedeags in water before placing them in DMHF (even glycerine is compatible with DMHF, see BAMEUL 1990). In any further manipulations later, it will also be appreciated that DMHF is reversibly water soluble at any time. Nevertheless, many collectors still use cheaper but more complicated or time-consuming methods to store aedeagus, e.g. using chloral hydrate, euparal, solacryl or Canada balsam, or various glycerine tubes pinned under the beetle label, etc. These different methods are more justified when depositing female genitalia. |

Preparation of larvae

Beetle larvae are prepared either as liquid preparations in glass bottles in which smaller tubes are placed or dry.

Liquid preparations

Liquid preparations are made as follows. We boil the larvae on a colander with hot distilled water and gradually transfer them through an alcohol series (50%, 70%, 80%) to 80% alcohol or we put them immediately from water into 4% formaldehyde. Place them in an epruvette, labelled with locality data, and place this in a wide-mouth storage bottle. The tube and the stock bottle are filled with preservative liquid (80% ethanol or 4% formaldehyde). The tube is closed with a wad of cellulose cotton and placed upside down in the stock bottle.

Dry preparations

Dry preparations are made as follows. Cut the dead larvae on the lateral or ventral side and remove the digestive tube. Then, molded into the desired shape, we place them in acetone for about half an hour and let them dry. Alternatively, large beetle larvae can be stuffed with cotton wool after all the guts have been removed, shaped to the desired form and left to dry.

Preparation by enclosing in an air chamber

Prepare according to the standard procedure for preparation by drying up to point 4.

Prepare a clean microscope slide of standard size 76 x 26 mm. Using an entomological pin, apply a microdrop of Hercules glue to the centre of the slide (the size of the drop is controlled by the size of the specimen). Using tweezers or a moistened brush (depending on the size of the specimen), transfer the specimen to the glue drop. Work so that the glue drop holds the area between the hips of the first and second pair of legs. Wait about 10 minutes for the glue to dry sufficiently. Then work the feet, body, head, antennae, antennae and mandibles so that the specimen is in its natural form, as when climbing. If the copulatory organs have been prepared, glue them to the glass next to the specimen.

As a protection from dust, place the glass with the specimen in a smaller paper box on a preparation mat and fasten between a few pins. Attach a note with locality data, close the box and leave at room temperature for about a week to dry.

Once the drying phase is complete, glue a phibre ring around the slide to form the walls of the future chamber. Glue the ring in the middle of the slide using Herkules glue. The thickness of the ring is chosen according to the height of the specimen. If necessary, more rings can be glued on top of each other to make the chamber tall enough.

To close the lacquer chamber, glue a clean cover slip to the phibre ring with Herkules glue. After the cover glass dries (after 24 hours), border 3 sides of the chamber with shrink wrap and fill the outer part of the chamber with Solakryl BMX on 4 sides. Pour the Solacryl very slowly to completely fill the space between the fibre ring and the shrink wrap. The density of Solacryl can be adjusted by diluting with xylene. Allow the Solacryl to dry well (about 24 hours). Once dry, remove the shrink film and use a razor blade or scalpel to remove any residue on the backing glass. Produce a 26 x 26 mm locality label and stick it with transparent adhesive tape on the left side of the slide. Once the species has been identified, produce a 26 x 26 mm determination label and adhere it with clear adhesive tape to the right side of the slide. While the locality label must be added to the specimen immediately, the determination label can be added later (after the specimen has been determined). Finally, we transfer the specimen prepared in this way to the storage box for microscope slides.

In this type of preparation, it is not strictly necessary to seal the chamber with Solacryl. After sealing the chamber with Hercules glue, you can add the locality and determination labels and store the specimen in the microscope slide box directly. However, a chamber made with Solacryl is more protected, especially against mechanical damage.

This type of preparation of the smallest specimens is particularly suitable for the preparation of rarer or type specimens due to the excellent protection of the specimen being prepared. However, it is more labour-intensive compared to preparation using adhesive labels.