2. Thorax (Thorax)

The thorax is the middle part of the body that bears three pairs of limbs and, in winged insects, two pairs of wings. It consists of three segments: the prothorax, mesothorax, and metathorax. Each segment carries a pair of legs. The mesothorax and metathorax also carry wings.

Basic concepts concerning the morphology of the thorax of the beetle

| Czech | English | Latin |

| Hruď | Thorax | Thorax |

| Předohruď | Prothorax | Prothorax |

| Středohruď | Mesothorax | Mesothorax |

| Zadohruď | Metathorax | Metathorax |

| Boční destička | Pleuron/pleura | Pleuron |

| Pleurální šev | Pleural suture | Sutura pleuralis |

| Pleurit | Pleurite | Pars pleuralis (Pleuritis) |

| Prosternum / Mesosternum / Metasternum | Prosternum / Mesosternum / Metasternum | Prosternum / Mesosternum / Metasternum |

| Prosternální výběžek | Prosternal process | Processus prosternalis |

| Štít | Protonum | Protonum |

| Štítek | Scutellum (scutellar shield) | Scutellum |

| Krovky | Elytron / Elytra (wing case) |

Elytrum / Elytra |

| Epipleura | Epipleuron | Epipleuron |

| Spirakulum | Spiracle | Spiraculum |

2.1 Prothorax (Prothorax)

The prothorax is the only thoracic segment that is freely movable. The dorsal part is called the protonum (pronotum).

The protonum is extremely important in terms of determination: its shape (square, transverse (wider than long), elongate, cordate, oval), sculpture (smooth, punctate, notched, with pits, with protuberances or with various growths, grooves on the sides), colouration and proportions in relation to the trunk and head are evaluated. In some families (e.g., the Carabidae), the characters on the thoracic shield are crucial for distinguishing genera and species.

Basic concepts related to the morphology of the thoracic shield (pronotum) of beetles

| Czech | English | Latin | Description |

| Přední úhly | Anterior angles | Anguli anteriores | Anterior corners of the shield |

| Zadní úhly | Posterior angles | Anguli posteriores | Posterior corners of the shield |

| Boční okraje | Lateral margins | Margines laterales | Lateral edges of the shield |

| Bazální okraj | Basal margin | Margo basalis | Posterior margin of the shield |

2.2 Mesothorax and metathorax (Mesothorax et Metathorax)

The mesothorax (mesothorax) and metathorax (metathorax) are largely covered by the elytra in beetles. The mesothorax bears forewings converted into elytra, while the metathorax bear blanched hindwings used for flight. A small triangular area called the scutellum is often visible on the dorsal side of the midwing, located between the bases of the trusses. Its shape and size are often important in distinguishing families.

Fundamental division: Adephaga vs. Polyphaga

The most critical morphological difference underlying the branching in taxonomic keys is found on the ventral side of the body, specifically in the region of the posterior hips (Metacoxae) and the first visible ventral article (Sternite I):

- Adephaga

The posterior hips are massive, enlarged and tightly fused to the first abdominal sternite. The first abdominal sternite is longitudinally divided and partially covered by this adhesion. In addition, a clear notopleural suture is present below the pronotal shield. - Polyphaga

The posterior hips are loose and smaller. They do not extend to the lateral margin of the body and the first abdominal sternite remains entire and undivided by the hips. The notopleural suture is absent in this suborder.

This morphological difference represents one of the most important autapomorphies of Polyphaga and is phylogenetically stable, making it the most accurate criterion for entry into the appropriate branch of the determinant key.

Comparison of morphological characters of Coleoptera suborders (Adephaga vs. Polyphaga)

| Morphological character | Suborder Adephaga (Carnivora) |

Suborder Polyphaga (Omnivorous) |

Significance for identification (Key) |

| Hind hips (Metacoxae) | Large, coalescing and dividing the first abdominal sternite. | Free, not extending to margin and not dividing first sternite. | Primary diagnostic sign (ventral view). |

| Notopleural suture | Present below the prothorax | Absent. | Additional sign. |

| Tarsal formula (standard) | Always 5-5-5 (without cryptic segments). | Very variable (5-5-5, 5-5-4, 4-4-4, 3-3-3). | Indicates limited Adephaga uniformity. |

| Antennae | Always filamentous (filiform) | Varied (lamellate, geniculate, serrate, ...). | Indicator of a huge ecological adaptation. |

Diagnosis of the prothorax and procoxal cavities

The prothorax, and especially its ventral part (prosternum), provides other important characters. The prosternal process is a structure that runs longitudinally between the anterior hips. The clavicles often distinguish the family by its shape and length. It may be reduced, almost absent, or it may be elongated and reach beyond the middle of the anterior hips.

Another criterion is the closure of procoxal cavities (Cavities Procoxales). The fossae may be either open or closed, often defined by the presence of a complete internal sclerotized bar. For example, in the family Dermestidae (Dermestidae, Bostrichiformia), the detailed structure of the prosternal process and the closure of the fossae are crucial for distinguishing subfamilies.

2.3 Elytra (Elytra)

Elytra are the most characteristic feature of the beetles. They are hardened, heavily sclerotized forewings that have lost the ability to fly and protect the blanched hindwings and rump. In flight, the trusses are spread laterally and the beetle flies using only the hind wings. Most beetles have elytra that are solid, convex and meet in a midline along their length, forming what is called an elytral suture. At rest, they cover the entire rump and most of the abdomen, protecting the folded second (blanched) pair of wings and internal organs beneath.

The elytra is usually hard, sclerotized, and completely cover the rump and membranous hindwings. The most notable exception to this rule is the family Staphylinidae (Infraorder Staphyliniformia). In Staphylinidae, the elytra is extremely short, revealing five to seven free, muscular and mobile abdominal sternites. This morphology is an immediate and highly diagnostic character that quickly places the beetle in this family.

In non-flying species (e.g., many large intestinal Carabidae), the elytra is serrated along the suture. This provides better protection against water loss (in desert and arid-loving species) and increases the overall strength of the carapace, but makes flight impossible.

The surface of the elytra may exhibit varying sculpture:

- Punctation (punctation, punctatio) - tiny dimples on the surface

- Grooves (striae, striae) - longitudinal indentations or grooves

- Interstices (intervals, intervalla) - raised bands between grooves

- Ribs (costae, costae) - longitudinal raised ribs

- Tubercles (tubercles, tuberculi) - conical or rounded projections

- Epipleura (epipleura, epipleura) - the curved lateral edge of the trusses

Grooves and dots

This is the most common and important type of sculpture.

- Striae: These are longitudinal, often fine but regular incisions extending from the base of the scrub to the tip. Typically there are 8-10 striae on each truss. The grooves are often interrupted by pits or dots.

- Punctation: The grooves and intergrowths may be covered with pits

- Punctate furrows: The furrow has pits that make it visible.

- Interstices (Intervals): These are the areas between the grooves. They can be smooth or self-dotted. The dots on interstices are often irregular.

- Interstices: These are specific pits in the interstices (e.g. in the 3rd, 5th and 7th interstices) from which setae often grow. These pits are important for identification in families such as the Carabidae.

Surface formations

- Smooth surface: shields without distinct sculpture, often shiny. Typical of aquatic beetles where they help reduce friction, or of some families with high gloss (e.g., some dwarfs).

- Granulation: the surface of the scrubs is covered with small, protruding granules or bumps. This gives the scrub a rough, matt appearance and increases mechanical protection.

- Ribs and battens: Distinctive, longitudinal, convex battens (carinae) which may either be continuous with the grooves or extend independently across the entire surface of the truss. They are often seen in cedar-bearing or some sweat beetles, where they increase the stiffness of the trunk.

Coverage and texture

In addition to the structure of the cuticle itself, the morphology of the scrub varies because of the coverage of hairs or scales.

- Pubescence: the elytra may be covered with short or long, erect or adherent hairs. These hairs may have a thermo-insulating function or may be involved in camouflage. For example, dense hairs are often seen in the chroostids (Melolonthinae).

- Scales: some beetles, especially the weevils (Curculionidae) and some Chrysomelidae, have scales densely covered with miniature, often coloured scales. These scales form complex colour patterns and are the main source of structural colouration.

Colouration and pattern

Elytra colouration is extremely variable and is due to pigments or structural colouration (produced by the interaction of light with the microscopic structures of the cuticle):

- Cryptic colouration (camouflage): brown, grey or black trusses help beetles blend in with tree bark, soil or foliage.

- Aposematic coloration (warning): Bright colors (red, yellow, black) and striking patterns (e.g., in sundews or blister beetles) signal to predators that the beetle is poisonous, inedible, or contains defensive chemicals.

- Structural colouration: produces the dazzling metallic and iridescent reflections (iridescence) that are typical of the dwarf beetles (Buprestidae) or some of the notched beetles (e.g. goldenrods).

Functional adaptations

- Flat vs. convex: Flat-bodied beetles, such as woodlice, can squeeze into narrow crevices under the bark. In contrast, strongly convex shapes (e.g., sun beetles) provide better protection.

- Cut-outs for flying: in goldfinches (Cetoniinae), the trusses have special cut-outs on the sides that allow them to fly with the trusses only slightly raised without having to open them completely. This allows them to maintain greater aerodynamic stability during flight.

- Respiratory protection (Diving beetles): In aquatic beetles (Diving beetles, Dytiscidae), the trusses form an airtight cover that encloses the air supply above the rump for underwater breathing.

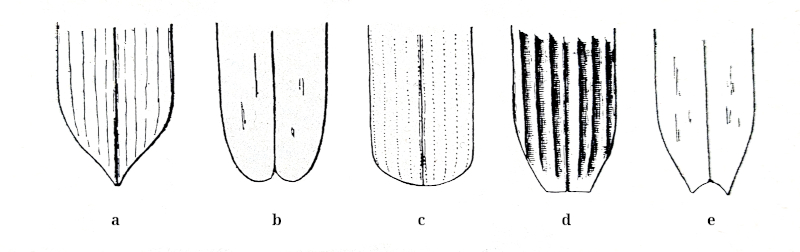

Different ways of ending the elytra

Legend: (a) spiked, finely grooved on the surface, (b) individually rounded, (c) collectively rounded, serially dotted on the surface, (d) truncate, keeled on the surface, (e) excavated

Legend: (a) spiked, finely grooved on the surface, (b) individually rounded, (c) collectively rounded, serially dotted on the surface, (d) truncate, keeled on the surface, (e) excavated

Elytra is key to species-level determination. They are assessed as:

- Length (whether they cover the whole rump or are shortened - e.g. staphylinids).

- Surface ornamentation (rows of dots, grooves, furrows - often 9 to 10 grooves on each scrub).

- Colouring and drawing.

2.4 Blanched hind wings (Alae)

Blanched hind wings, also called metathoracic wings or alytera, are the primary flight organs in beetles. They are located on the hindwing below the heavily sclerotized and modified forewings - the elytra. Their main morphological feature is a thin, transparent membrane and a complex but precise system of veins (venation), which also allows the wing to fold into a compact shape. The wing venation is also of taxonomic importance. In some species, the hind wings are reduced or missing entirely, resulting in an inability to fly.

Morphological structure and venation

The wing of the beetle is divided into several fields defined by longitudinal veins. The basic plan of the venation corresponds to the general scheme of insect wings:

The wing of the beetle is divided into several fields defined by longitudinal veins. The basic plan of the venation corresponds to the general scheme of insect wings:

- Anterior margin (Costal Margin): reinforced by Costa (C) and Subcosta (Sc) veins.

- Radial and Medial Array: Forms the main bearing surface. Includes the Radius (R) vein, often with an anterior (R1) and radial-sector (Rs) branch, and the Media (M) vein. These veins tend to be the strongest.

- Cubital field: Contains the vein of Cubitus (C).

- Anal / Clavicular Area (Claval Area): The posterior and usually largest part of the wing, which is crucial for folding. It is made up of several anal veins (A1, A2, A3). This area is separated by the claval furrow.

The veining is usually described using a standardized system (Comstock-Needham system) where each vein has its own abbreviation (e.g. R, M, Cu) and possibly branches (e.g. R1, Rs).

Overview of the standard abbreviations used to refer to the veining of insect wings

| Abbreviation | Czech | English | Latin | Description |

| C | Kosta | Costa | Costa | A thick, usually unbranched vein forming the leading edge of the wing. |

| R | Rádius | Radius | Radius | One of the strongest veins. It is located behind Costa and divides into R1 (front branch) and Radius sector (Rs). |

| M | Médie | Media | Media | A median vein, often running through the middle of the wing. In beetles it is usually reduced, and may be divided into an anterior (MA) and posterior (MP) branch. |

| Cu | Kubitus | Cubitus | Cubitus | Lies behind Media. It is typically divided into Cubitus anterior (CuA) and Cubitus posterior (CuP). It is often distinct. |

| Sc | Subkosta | Subcosta | Subcosta | It lies just behind Costa (C). It is often reduced and merges with R. |

| A | Anální žíly | Anal veins | Anal veins | Veins in the posterior, usually fan-shaped part of the wing (in the anal region) that folds when folded. |

Oblongum and other formations

- Oblongum (rectangular cell)

- Unlike the above terms that refer to veins, the term oblongum refers to a closed cell (field) in the veining, not the vein itself.

- It is usually a rectangular or trapezoidal formation that is typical of the venation of some groups of beetles (e.g., the cutworms, Carabidae).

- This cell is bounded by parts of the R, M and Cu veins or their junctions. Its shape and presence are important taxonomic characters.

- Pterostigma: A thickened, often pigmented area on the leading edge of the wing (between C and R) that stabilizes flight.

- Junctions (Cross veins): Short veins that connect the main longitudinal veins (e.g. r-m connects R and M). They delimit the individual wing cells.

The fundamental adaptation of blanitic wings is the folding mechanism. When resting, the wings must be folded under the trusses. This process is made possible by two main elements:

- Transverse Fold: Most beetles have a flexible zone across the wing (often between Cu and A1) that allows the wing to fold in a forward direction.

- Longitudinal Fold: Occurs in the anal field along the claval groove.

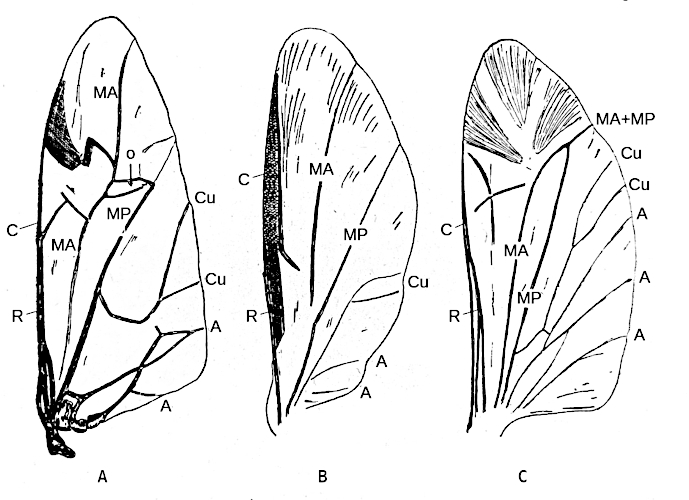

Differences in Adephaga and Polyphaga wings

Wing structure is one of the key features distinguishing the two main suborders of beetles:

| Character | Adephaga (Carnivorous beetles) | Polyphaga (Omnivorous beetles) |

| Veining | Fuller and more complex, clearly defined radial, medial and cubital veins. | Strongly reduced, especially in the anal field. Often lacking some branches. |

| Wing cells | Presence of two or more closed cells near the middle of the wing, often due to transverse connections between R and M. | The venation is more open, closed cells are less frequent or absent. |

| Folding | Folding is often more complex, using multiple longitudinal folds. The wing is stronger. | Typically, folding is rather simpler with a single, distinct transverse fold line in the centre of the wing (e.g. in weevils). |

| Anal field | Large and well developed. | Often reduced or fused. |

Wing venation: difference between Adephaga and Polyphaga

Legend: (A) Adephaga type: many transverse veins. There is an oval chamber oblongum(o) between MA and MP veins; (B) type Staphylinidae: few transverse veins, MA and MP veins arising freely on outer wing margin; (C) type Cantharidae: few transverse veins. MA and MP veins join before the end and emerge on the wing margin as a common vein; C = costa, R = radius, MA, MP = media, Cu = cubitus, A = anales

Legend: (A) Adephaga type: many transverse veins. There is an oval chamber oblongum(o) between MA and MP veins; (B) type Staphylinidae: few transverse veins, MA and MP veins arising freely on outer wing margin; (C) type Cantharidae: few transverse veins. MA and MP veins join before the end and emerge on the wing margin as a common vein; C = costa, R = radius, MA, MP = media, Cu = cubitus, A = anales

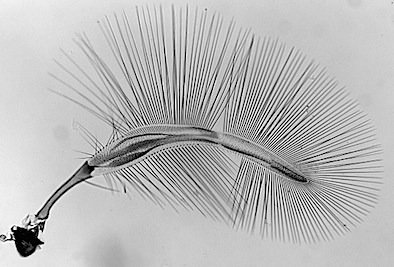

Peculiarities of feather wings (Ptiliidae)

Feather wings, representatives of the family Ptiliidae, are among the smallest beetles in the world (size often less than 1 mm). This miniaturization is related to the extreme specialization of their flight apparatus. Their blanched wings are reduced to narrow, oar-like formations called pteryla.

The main flight surface is not made up of a membrane, but of long, fine furrows (setae) that line the edges of the wing. These ribs increase the effective wing area and minimize air resistance, allowing the beetles to fly in viscous environments at a microscopic level, often using a specific clapping flight mechanism. Feather wings thus represent the pinnacle of evolutionary adaptation to flight on an extremely small scale.

For those interested in this family, I attach an article that reports on interesting research on the flight capabilities of Ptiliidae representatives.

![]() A new flight style that helps the smallest beetles stand out

A new flight style that helps the smallest beetles stand out

The wings of the Ptiliidae

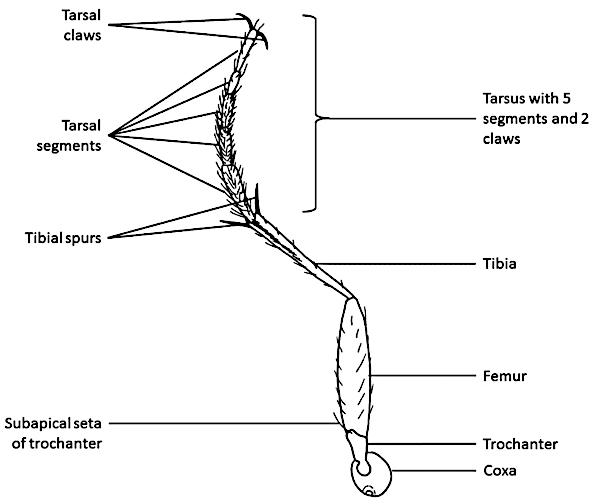

2.5 Legs (Pera)

The beetles have three pairs of legs arising from the thorax. Each leg consists of several links.

Basic concepts related to the morphology of the beetle's legs

| Czech | English | Latin |

| Noha | Leg | Pera |

| Kyčel | Coxa | Coxa |

| Příkyčlí | Trochanter | Trochanter |

| Stehno | Femur | Femur |

| Holeň | Tibia | Tibia |

| Holenní ostruhy | Tibial spurs | Calcaria tibiae |

| Chodidlo | Tarsus | Tarsus |

| Článek chodidla | Tarsomere | Tarsomere |

| Drápky na chodidle | Tarsal claws | Ungues tarsales |

| Onychium | Onychium | Onychium |

Leg composition of the beetle

The legs are modified according to the way of life:

- Cursorial legs (pedes cursorii) - long and slender for fast running

- Fossorial legs (pedes fossorii) - robust with flattened tibial links for digging

- Saltatorial legs (pedes saltatorii) - with reinforced hind legs for jumping

- Natatorial legs (pedes natatorii) - flattened with rows of hairs for swimming

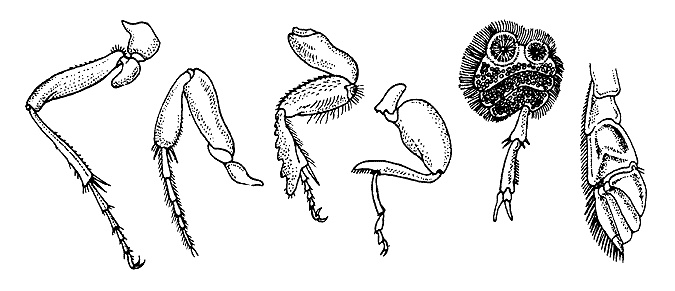

Overview of basic types of beetle legs

Legend: walking, swimming, digging, jumping, suction cup, paddle-shaped

Legs and tarsal classification - the phenomenon of cryptic links

The most important identifying feature on the legs is the number of foot links (tarsomeres). Detailed study of the tarsals (feet) is essential for accurate identification of families, especially within the suborder Polyphaga. The ability to correctly apply the tarsal pattern is often the point where the amateur entomologist differs from the expert.

The tarsal formula (tarsal formula) is written as the number of cells on the anterior-mid-posterior leg, for example, 5-5-5 (pentameric), 5-5-4 (heteromeric), or 4-4-4 (tetrameric). This formula is essential for distinguishing families. Some families appear to have one less link because one link may be very small and hidden (crypto-pentameric).

The plesiomorphic formula (5-5-5), which most Adephaga and many Polyphaga families (e.g. Elateridae, Scarabaeidae) have, has five articles on each tarsus.

The 5-5-4 formula is characteristic of, for example, the superfamily Tenebrionoidea (e.g., Tenebrionidae).

The phenomenon of pseudotetramerism is essential for the largest and most diversified families of the infraorder Cucujiformia (e.g., Chrysomelidae, Cerambycidae, most Curculionidae). Although the tarsus appears to be four-segmented (apparent pattern 4-4-4), it is actually five-segmented (true pattern 5-5-5). The fourth segment (tarsomere 4) is extremely reduced in size (cryptic) and is firmly hidden within a notch or lobe of the strongly developed third segment (tarsomere 3). For determination, it is necessary to verify the presence of this cryptic fourth segment under the microscope, which reliably assigns the beetle to the appropriate Cucujiformia group.

A similar principle applies to the family Coccinellidae. In these, the apparent pattern is 3-3-3, but the true pattern is 4-4-4. In this case, the cryptic and difficult to see third segment is hidden in the lobe of the second segment.

The phenomenon of pseudotetramerism is strongly associated with phytophagia. Large and lobed tarsal segments (such as tarsomeres 3) provide a greatly increased adhesive surface, which is crucial for movement over smooth plant surfaces (leaves, stems). The presence of the cryptic link provides optimum flexibility for claw attachment without compromising adhesion efficiency. Recognition of this convergent character is crucial for correct assignment to phylogenetically advanced lineages of herbivorous beetles (Chrysomeloidea, Curculionoidea).

Sexual dimorphism

In the males of many species, the forefoot segments are expanded and provided with attachment barbules. This character is used to distinguish the sexes and often related species.

Tarsal patterns (Formulae) and cryptic articles in key families of the Czech Republic

| Tarsal formula (apparent) |

Tarsal Formula (true) |

Morphological characteristics |

Examples of key key families of the CR |

| 5-5-5 | 5-5-5 | All articles clearly visible. | Adephaga (Carabidae) Elateriformia (Elateridae) |

| 5-5-4 | 5-5-4 | Anterior and middle 5-membered, posterior 4-membered. | Tenebrionoidea (Tenebrionidae) |

| 4-4-4 | 5-5-5 | Pseudotetramerous: 4. article is cryptic, hidden in lobe of 3rd article. |

Chrysomelidae, Cerambycidae, Curculionidae (most) |

| 3-3-3 | 4-4-4 | Pseudotrimerous: 3. article is cryptic, hidden in lobe 2 of article. |

Coccinellidae |

Significance for determination:

- Shape and proportions of pronotum ( length : width, edges, projections ) - e.g. in genera of the family Carabidae.

- Structure of elytra (e.g. length, whether they reach to the end of the abdomen, whether they are truncated) - in some representatives the elytra are truncated and part of the rump is exposed.

- Leg shape (e.g., elongated femora in jumping beetles, adaptations for swimming).