1. Head (Caput)

1.1 Position and function

The head is the first compartment of the body, located in front of the thorax and is either loosely connected to the thorax by the cervix or by a narrow neck (cervix). It contains sensory organs such as the eyes (oculi) and antennae (antennae), the oral organs (mandibulae, maxillae, labium) and, internally, the brain.

Functionally, the head provides food intake, mechanical processing, perception of the environment (smell, touch), and also provides support for various taxonomically significant structures (e.g., shape of clypeus, arrangement of antennae). For example, in raptors, the mandibles may be greatly enlarged.

Basic concepts related to the morphology of the beetle head

| Czech | English | Latin |

| Hlava | Head | Caput |

| Tykadlo | Antenna (pl. Antennae) | Antenna / antennae |

| Oko (složené) | Compound eye | Oculus (pl. oculi) |

| Čele | Forehead | Frons |

| Temeno | Vertex | Vertex |

| Tvář | Cheek | Genae |

| Přední štít | Clypeus | Clypeus |

| Horní pysk | Upper lip | Labrum |

| Kusadla | Mandibles | Mandibulae |

| Čelisti | Maxillae | Maxillae |

| Dolní pysk | Lower lip | Labium |

| Čelistní makadla / Pysková makadla | Palps maxillary / Palps labial |

Palpus maxillaris / Palpus labialis |

| Oko (jednoduché) | Ocelli | Ocelli |

| Spánek | Temple | Tempus |

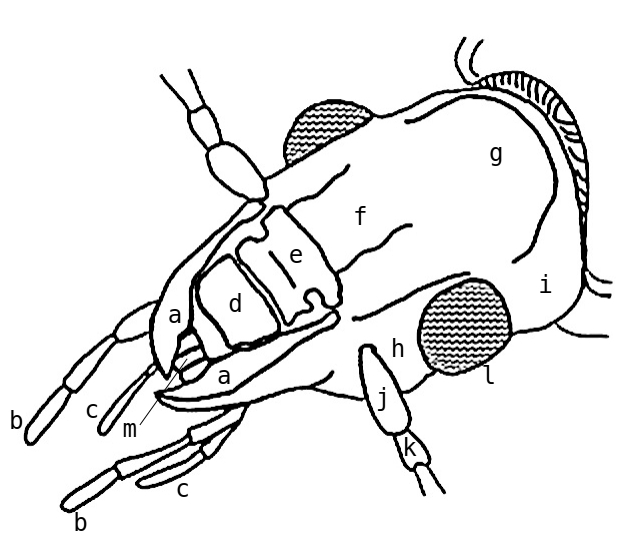

Dorsal side of the beetle head and its basic parts

Legend: (a) mandible (mandibula), (b) maxillary palp (palpus maxillaris), (c) labial palp (palpus liabialis), (d) upper lip (labrum), (e) clypeus (clypeus), (f) forehead (frons), (g) vertex (vertex), (h) cheek (gena), (i) temple (tempus), (j) scape (scapus), (k) pedicel (pedicellus), (l) eye (oculi), (m) lower lip (labium)

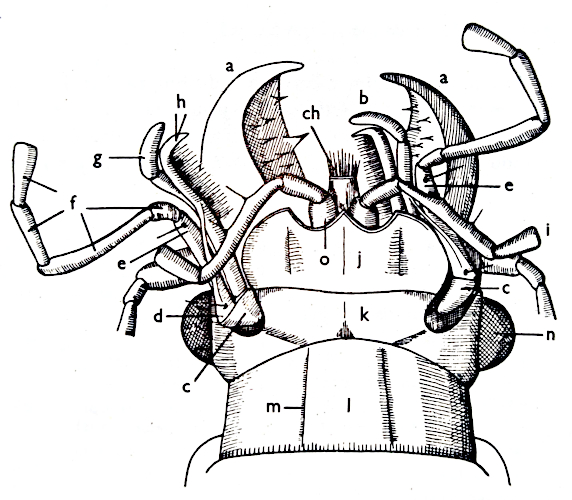

Ventral side of the beetle head and its basic parts

Legend: (a) mandibles (mandibulae), (b) maxillae (maxillae), (c) maxillary base article (cardo), (d) maxillary trunk (stipes), (e) article bearing the maxillary macula (squama palpigera), (f) individual articles of the maxillary maculae, (g) external maxillary sulcus (galea / lobus externus), (h) internal maxillary sinus (lacinia / lobus internus), (ch) hypopharynx (hypopharynx), (i) labial palp (palpus liabialis), (j) mentum (mentum), (k) submentum (submentum), (l) gula (gula), (m) gular suture (sutura gularis), (n) compound eyes (oculi compositi), (o) root (origin) of labial maculae

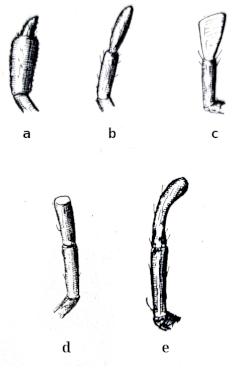

Different types of the last macular articulation

Legend: (a) ascine, (b) ovoid, (c) secant, (d) truncate, (e) crescentic

Unlike the thorax and occiput, the head is not segmented. Its shape and orientation are important determinants - it can be prognathic (forward facing), hypognathic (downward facing) or opisthognathic (backward facing). Similarly, the shape of the forehead and its ornamentation (grooves, pits) are used for species determination. In some groups, the head is elongated into a nasal (rostrum) (e.g., rhinocerotidae Curculionidae).

The position of the head in relation to the longitudinal axis of the body is an important character:

- Prognathous: The head faces forward along the body axis, with the mouthparts directed forward. This type is typical of predatory and scavenging groups that actively pursue food (e.g., Carabidae, Silphidae).

- Hypognathous: The head is turned slightly downwards perpendicular to the body axis and may be partially hidden under the pronotum. Common in herbivorous beetles and weevils (Curculionidae, Staphylinidae).

- Opisthognathous: head points backwards under the body at an acute angle (less common in the order Coleoptera) (Chrysomelidae - Galerucinae).

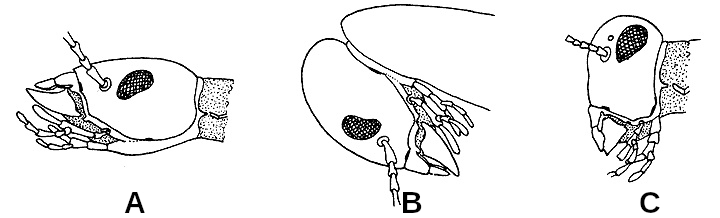

Position of the head relative to the longitudinal axis of the body

Legend: (A) prognathous, (B) opisthognathous, (C) hypognathous

Almost all beetles have a biting mouthparts. Its shape is modified according to the type of food:

- The mandibles (mandibulae): they are often massive and heavily sclerotized (especially in predatory species such as mealworms) or, conversely, elongated (in weevils). Their shape and serrations are important for identification at the genus and species level

- Maxillae (maxillae) and lower lip (labium): They bear three- to four-membered maxillary maculae (palpi maxillares), the number and shape of which are taxonomically important (e.g., in the family Hydrophilidae). In specialized groups, such as Myxophaga, the mandibles are equipped with large chewing surfaces (molae) and setal brushes, indicating adaptation to the collection of delicate food such as algae.

1.2 Eyes (Oculi)

Beetles have compound eyes (oculi compositi), which consist of many individual facets called ommatidia. The number of ommatidia is highly variable, ranging from a few to thousands. The number of ommatidia affects the resolution - the more of them, the sharper the resulting image. Each ommatidium functions as a separate eye and consists of the following main parts:

- Cornea: The outer, transparent surface that is actually a converted cuticle. It forms a mosaic-like grid (facet) on the surface of the eye.

- Crystalline cone: A luminous body located under the cornea, usually made up of four transparent cells.

- Retina: A layer of light-sensing cells (photoreceptors) containing a rod-shaped body (rhabdom) that senses light.

- Pigment cells: surround the ommatidia and prevent light from penetrating into adjacent ommatidia, thus providing separate perception (see below).

Through these structures, beetles perceive the surrounding world as a mosaic of light and dark points. The compound eyes are excellent for detecting movement. The eyes can be whole, cut through the antennal socket, or divided into two parts (e.g., whirligigs). In some species, the eyes are divided or notched, while in others, living in caves or leading a less active life, the eyes may be reduced or completely absent.

Image perception

The insect eye produces a mosaic image (raster). Each ommatidium perceives only a small "pixel" (varying degrees of clarity) from the direction it is facing, and the insect's brain assembles these pixels into an overall image.

Two main types of compound eye are distinguished according to the arrangement of the ommatidia and pigment cells, both of which are also found in beetles:

- Apositional eye structure (Diurnal adaptation)

- Occurs predominantly in diurnal beetle species.

- The pigment cells closely surround the rhabdom, so that light from one ommatidium does not penetrate into the adjacent ones.

- A sharp mosaic image is formed, but with lower light sensitivity.

- Superpositional structure of the eye (Night/Twilight adaptation)

- Occurs mainly in nocturnal and twilight species of beetles (e.g. some beetles or moths).

- The pigment is contracted, allowing light rays to enter adjacent ommatidia and join on a single retina.

- The result is a brighter image (higher sensitivity) but with lower resolution and less noticeable detail.

Colour vision in beetles

Beetles, like most insects, perceive colors differently from humans. Their colour vision is usually shifted to shorter wavelengths, due to the types of photopigments (opsins) contained in the photoreceptor cells (rhabdomeres) within the ommatidia.

1. Ultraviolet vision (UV)

The most significant difference from human vision (which perceives wavelengths from about 400 to 700 nm) is the ability to perceive ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

- Beetles have receptors sensitive to UV light, with maximum sensitivity typically around 340 - 360 nm.

- Biological significance: seeing UV light is crucial for beetles (and insects in general) to

- Orientation: UV light is used for navigation (e.g. using sunlight or polarized light).

- Foraging: many flowers have UV markings and patterns (nectar guide lines) that are invisible to the human eye, but which contrastingly signal the location of nectar and pollen to pollinators, including beetles.

- Communication/Mate selection: the UV reflectance of the beetle cuticle may play a role in signalling between the sexes and is thus important for mate recognition.

2. Types of visual pigments (Dichromatic or Trichromatic vision)

Most insects use a combination of two or three types of photopigments to produce color vision.

- Dichromatic vision. Their spectral sensitivity peaks in the regions

- 340 - 360 nm (Ultraviolet)

- 520 - 550 nm (Green-Yellow)

- Trichromatic vision: many insect species are considered trichromatic, using three maxima of sensitivity: UV, Blue and Green.

3. Sensitivity to longer wavelengths (Red)

Insects generally have low sensitivity to longer wavelengths, corresponding to the color red (above about 600 nm).

- Green and blue light: Receptors with maximum sensitivity are usually found in

- The blue region (approx. 440 nm)

- Green region (approx. 530 nm)

- Red: Most beetles, like other insects, do not perceive the color red as clearly as humans do, or cannot distinguish it at all (similar to colorblind humans). However, there are exceptions and differences between different families of beetles, and some species may have receptors with sensitivity shifted to 700 nm.

Comparison of human and typical insect vision

| Wavelength (nm) |

Human vision | Typical insect vision (including beetles) |

| < 400 | Invisible (UV) | Very sensitive (UV) |

| 400 - 500 | Purple, Blue | Sensitivity to Blue |

| 500 - 600 | Green, Yellow | Sensitivity to Green |

| 600 - 700 | Orange, Red | Low / Missing Sensitivity |

Some species of beetles also have simple eyes (ocelli), which are located on the top of the head. However, they are not as common in adult beetles as in other groups of insects (e.g. bees or dragonflies). In contrast, beetle larvae do not have compound eyes, but only smaller simple eyes called stemmata (or lateral ocelli), which form only a crude image of their surroundings.

1.3 Antennae (Antennae)

Antennae are paired sensory organs located mostly on the front edge of the head. They are primarily olfactory organs, but also serve to sense touch, temperature, and humidity. They typically consist of 11 cells, although the number can vary. The antennae show a huge variation in shape, making them an important determinant. They consist of a basal cell called the scapus, a second cell called the pedicellus, and a flagellum composed of additional cells.

Basic concepts related to the morphology of beetle antennae

| Czech | English | Latin |

| Nástavec | Scape | Scapus |

| Stopka | Pedicel | Pedicellus |

| Bičík | Flagellum | Flagellum |

The scape (Scapus) is the first (basal) link of the antennae, which connects the antennae to the head. It is formed by an insertion into the antennal socket (torulus). It is usually the most bulky and often strikingly shaped. It allows movement of the entire antenna by muscles that clamp inside the head capsule.

The pedicel (Pedicellus) is the second link between the extensor (scape) and flagellum (flagellum). Inside is the Johnston's organ, a sensory organ that responds to vibration and movement of the antennae. It is usually short and less mobile than the pedicle. It is important functionally (sensory), not so much morphologically for species identification.

The flagellum (Flagellum) makes up most of the length of the antennae, consisting of several to many links called flagellomeres (flagellomerae). It is the most variable part - it can be filiform, ridged, saw-like, club-shaped, fan-shaped, etc. It contains sensory receptors for smell, touch and the perception of moisture and temperature. The shape of the flagellum is an important determinant in beetle systematics.

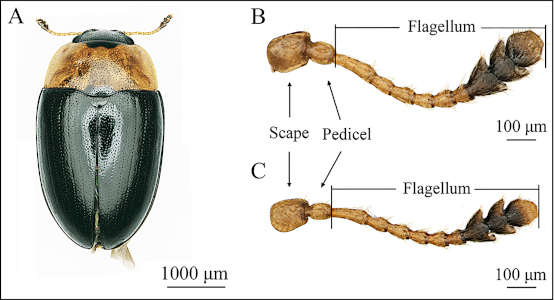

The composition of the antennae of the beetle

Legenda: The antennae of adults male and female of T. ainonia are composed of scape, pedicel and flagellum (Figs 1; 2A and 2B, male). The scape is cylindrical and stout, while the pedicel is oval, and significantly narrower than the scape (Fig 2C, female). The flagellum consists of 9 flagellomeres (F1–F9), and the F1 is the longest flagellomere. The shape of F2–F6 is similar as a short cylinder. The shape of F7, F8, and F9 were nearly triangular, semilunar, and circular, respectively.

The main types of antennae include:

- Filiform antennae (antennae filiformes) - all links approximately the same thickness

The cells are cylindrical and uniform in thickness. They are plesiomorphic and a permanent feature of the suborder Adephaga and, for example, the family Elateridae or Cerambycidae. - Clavate (stamens) antennae (antennae clavatae) - terminal articles thickened into clavate

They have distal (terminal) links that gradually enlarge towards the tip, forming a club-like shape (resembling a baseball bat or golf club). This terminal mallet is looser and the articles enlarge gradually (e.g. Coccinellidae, Cleridae or some Tenebrionidae). - Capitate (bulbous) antennae (antennae capitatae) - terminal articles abruptly expanded into a head

They have last articles that are abruptly and greatly expanded, forming a globose or strongly compact head (Lat. caput = head). These articles form a distinct, compact stamen that is clearly separated from the rest of the antenna, in contrast to the gradual enlargement in club-shaped antennae (e.g., Nitidulidae, Dermestidae, Histeridae). - Lamellate antennae (antennae lamellatae) - terminal segments expanded into leaflets

Terminal segments are flattened into thin, folded petals (lamellae). This is an autapomorphy of the superfamily Scarabaeoidea (Scarabaeidae, Lucanidae, Geotrupidae). - Pectinate (ridge) antennae (antennae pectinatae) - articles with projections (on one or both sides) resembling the teeth of a ridge

In beetles, such antennae are often found in males - probably for better olfaction, e.g. to locate females or scent signals (Pyrochroidae, Chrysomelidae, some Elateridae). - Serrate antennae (antennae serratae) - triangular-shaped articles, resembling saw teeth

The articles have short triangular projections on one side, resembling saw teeth. Characteristic of the infraorder Elateriformia and e.g. some representatives of Cerambycidae or the subfamily Bruchinae. - Geniculate antennae (antennae geniculatae) - with a sharp bend (typical of weevils); first article elongated, antennae refractile

Scapus (first article) is long, whereupon the antennule bends sharply (like a knee). They are typical of the superfamily Curculionoidea (Rhinocerotidae), Lucanidae and some Pselaphinae. - Moniliform antennae (antennae moniliformis) - individual antennae segments are spherical (round) or cylindrical (a special type of club-shaped or headed antennae)

The links are connected by narrow necks, making them look like strung beads. All the links, except for the base (scapus) and sometimes the second (pedicel), are similar in size, not forming such a distinct stamen (as in capitate or clavate types). For example, the genus Rhysodes.

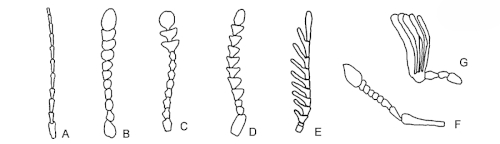

The basic types of antennae in the order Coleoptera

Legend: (A) filiform, (B) clavate, (C) capitate, (D) serrate, (E) pectinate, (F) geniculate, (G) lamellate

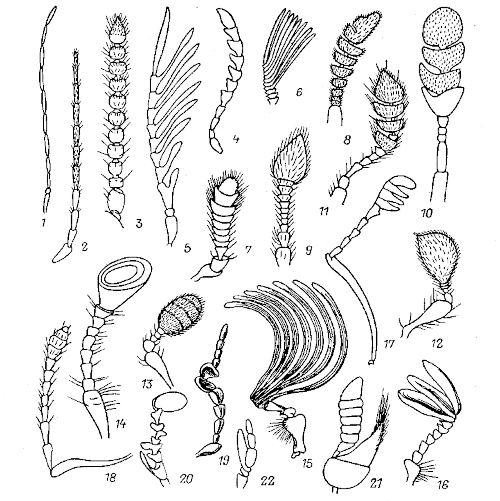

Different variants of Coleoptera antennae

Legend: 1 - filiform (Obrium), 2 - setiform (Carabus), 3 - moniliform (Rhysodes), 4 - serrate (Bruchus), 5, 6 - pectinae (5 - Kyotorhinus, 6 - Rhipidius), 7 - squamate (Ammophthorus), 8 - fusiform (Trogoderma), 9 - clavate with indistinct and unsegmented club (Trinimum), 10 - clavate with loose club (Triarthron), 11 - clavate with interrupted club (Anisotoma), 12 - club distinct and unsegmented (Xyloterus), 13 - compact club (Cryphalus), 14 - encased club (Xyloterus), 15, 16 - lamellate (15 - Polyphylla, 16 - Pheneomeris), 17 - lamello-geniculate (Lucanus), 18 - clavate-geniculate (Scytropus), 19-21 - irregular (19 - Meloe, 20 - Cerostoma, 21 - Gyrinus), 22 - chelate (Stylops).

The differential morphology of antennae among suborders reflects a fundamental ecological division. Adephaga, as predominantly predators, have retained a simple filiform structure that serves the basic sense of touch and smell required for rapid locomotion. In contrast, Polyphaga occupied a vast array of specialized ecological niches (xylophages, coprophages, saprophages), leading to extreme adaptive radiation of antennae. An example is the lamellate antenna in Scarabaeoidea, which is highly efficient at detecting odors (e.g., pheromones or droppings) at a distance. The knobby antenna in Curculionidae (weevils) is in turn associated with a specialized phytopathogenic lifestyle; the kink allows more precise manipulation of the antenna when ovipositing or feeding on plants, while the rest of the head is extended into a groove (rostrum).

The small morphological characters on the head tend to be important in identifying beetles:

- the shape of the antennae (e.g. filamentous-filiform, clavicon-clavicon)

- the number of antennal segments and their arrangement

- proportions and shape of the frontal plate (clypeus)

- condition and shape of mandibles (e.g. predators vs. herbivores)

- presence or absence of grooves, carline (longitudinal keel-like or ridge-like projections) or foveae (small pits)