Identification keys

A determination key, also referred to as a determination key in taxonomy, is much more than an ordered list of characters. It is a formalized, structured system that serves as a synthesis and standardized presentation of the results of extensive taxonomic research. Its primary function is to provide a systematic and reproducible algorithm that allows the user to assign an unknown biological object, in this case a specimen of the order Coleoptera, to an already validly defined taxon (e.g. genus, species or subspecies).

A determination key, also referred to as a determination key in taxonomy, is much more than an ordered list of characters. It is a formalized, structured system that serves as a synthesis and standardized presentation of the results of extensive taxonomic research. Its primary function is to provide a systematic and reproducible algorithm that allows the user to assign an unknown biological object, in this case a specimen of the order Coleoptera, to an already validly defined taxon (e.g. genus, species or subspecies).

The principle of the standard key is a series of successive decisions: the user chooses the one that better matches the subject from the mutually exclusive options offered. In this way, the range of possible taxa is narrowed step by step until a single species is reached. The key algorithm is usually designed to break down a larger set of taxa into smaller parts suitable for a quick decision. Keys are indispensable in systematic biology and taxonomy, especially for species-rich groups such as the order Coleoptera. Traditional keys used to be printed and static, but today there are interactive digital keys that make the process easier.

1. Linear Keys (Single-access Keys)

Linear keys are the most traditional and most widely used type, where the sequence of steps is fixed by the author of the key. The user must proceed sequentially from the first point to the last point, which leads to the determination of the taxon.

1.1 Dichotomous key

The dichotomous key is the most common and most transparent type. The principle of dichotomous selection is that at each step there is always and only a choice between two exclusive options - the so-called couplets (e.g. YES/NO, A/B). The user compares the insect under study with both statements in the couplet and selects the option that matches - this will refer the user to the next relevant step of the key. This strict structure significantly minimizes errors caused by simple orientation or navigation in the key. The most efficient form of linear key is the bracketed key, where opposing pairs of characters are placed immediately below each other and are symbolically distinguished (e.g., 9a and 9b). Dichotomous keys are popular for their simplicity and clarity: they offer only two choices at each step, minimizing user hesitation. For example, a simplified key to insect orders might begin as follows:

| 1a. Two pairs of blanite wings ............ go to 2 1b. Only one pair of blanitic wings (the other pair is converted to trusses or missing) .... go to 29 2a. Fore and hind wings identical in shape and size ............ go to 3 2b. Forewings different from hindwings (e.g. converted to trusses) ..... go to 18 3a. ... (more resolution) 3b. ... (further resolution) |

1.2 Polytomic key

If an option in a key is made up of more than two options, it is a polytomous key. Although strict dichotomy is recommended for its clarity, there is a compelling argument for using polytomy. Most biological traits, such as color or variable numbers of segments, are not inherently binary. Trying to convert these traits into a strictly dichotomous structure leads to artificial and unnecessary complication of the trait description. Polytomy (e.g., 1a trusses green; 1b trusses blue; 1c trusses red) is more natural for such characters. In expert practice, it is recommended to use a strict dichotomy where it is appropriate to the nature of the trait (e.g. presence/absence), and polytomy where it is necessary for a faithful description of variable states.

2. Interactive Keys (Multi-access Keys)

Interactive, computational keys, often implemented on platforms such as Lucid, are revolutionizing the determination process. While linear keys force the user to follow a fixed sequence, interactive systems allow the user to choose the state of a character in any order.

The user chooses feature states from a branching list (feature tree). After each selection, the system automatically moves all taxa that do not have the selected feature combination to the "Entities Discarded" panel. One of the biggest advantages of these systems is their resistance to incomplete samples. If a key character in a linear key is corrupted (e.g., for a broken head), the determination ends. The interactive key allows this feature to be ignored and other available features to be used.

This flexibility is invaluable for working with field material. However, the user must be cautious and always compare his specimen with the accompanying descriptions (fact sheets), as the automatic exclusion of taxa may mask an error in the interpretation of the selected character.

3. Other key types

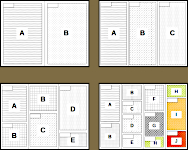

3.1 Tabular keys

Tabular determination keys are an alternative to the classical dichotomous keys and belong to the so-called static multi-entry keys. They are mainly used in entomology where large numbers of characters need to be compared quickly or where species differ from each other in only a few details.

In contrast to the classical dichotomous key, which guides the user step by step, a tabular key shows an overview of all characters at once. Thus, it functions more like a matrix of characters and species, as the following example shows:

| Character / Species | Type A | Type B | Type C | Species D |

| Shape of antennae | filamentous | club-shaped | sawtooth | filamentous |

| Colour of trusses | black | reddish brown | black | yellowish |

| Number of antennae links | 11 | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| Presence of wings | yes | yes | no | yes |

The user observes his specimen and gradually crosses out species that do not match the selected traits. Eventually he is left with only one (or a few) options.

This method is very clear, especially for smaller groups of species (e.g. up to 10 - 20 species), and allows a quick visual check of all the characters at once. In essence, it is a comparison table that allows characters to be worked with in parallel, rather than sequentially. Characters can be described verbally (e.g. "color of scrubs: brown"), numerically (e.g. "number of antennae cells: 11") or by symbols (e.g. ✓ / ✗ for the presence of a particular structure). In printed form, the table is usually accompanied by explanatory notes and illustrations of the symbols.

3.2 Visual keys

In addition to textual keys, there are also visual identification aids. These may take the form of picture keys or atlases, where characters are not distinguished verbally but by illustrations or photographs. Such keys are illustrative and easy to understand even for beginners, but there is a risk of relying solely on the visual presentation of the character. Experience has shown that visual keys without a textual explanation of the nature of the sign can lead to misinterpretation even by experienced users. Given the dependence of entomology on small, technical and often non-intuitive microscopic characters (such as genital shape or pubic specificity), it is essential that illustrations in keys are always accompanied by detailed technical descriptions and terminology.

Visual and interactive keys can be very useful for initial orientation, but the classic textual dichotomous keys still dominate the detailed identification of species, especially in the scientific literature.

4. The procedure for identifying insects

A systematic procedure and careful observation are required to successfully identify a specimen. First, we check the condition of the specimen - an adult with the best preserved characters is ideal (a damaged or incomplete specimen may make determination difficult or impossible). We then select a suitable identification key. If we do not know to which taxonomic group the specimen belongs, we start with a general key (e.g. a family key) to place the specimen in a broader group. Once we have identified the family (e.g. Carabidae, Cicindellidae, Histeridae, etc.), we continue with a more specialized key for that group - there are often keys for individual families, subfamilies or tribes. Such multi-tiered determinations are common, as a one-size-fits-all key to all beetle species would be too branching and cluttered.

Knowledge of specific morphological terminology is also essential for reliable determination, especially in taxonomically difficult groups such as the Coleoptera. Distinguishing closely related species often requires quantification, i.e. measurement of body proportions. Microscopic examination is often necessary for species identification, especially in taxonomically difficult families. Without preparation and microscopic inspection of subtle characters such as various spines or specific pubescence, determination cannot be reliably completed. In systematic coleopterology, the preparation of chitinized parts of the genitalia, especially the aedeagus in males, is standard. This step is often critical as the external morphology may not be sufficient.

The actual use of the key is done step by step. We read carefully the two alternative descriptions in each step (couplet) and compare them with the character of the insect under study. For example, the key may begin by distinguishing whether or not the insect has wings; if our specimen has wings, we follow the instructions for the "has wings" variant, if it does not, we follow the "wingless" variant. It is important to study both options, even the one that doesn't fit at first glance - this is the only way to make sure that we have understood the definition of the character correctly. Sometimes the key gives clarifications or exceptions in parentheses that should be taken into account. After selecting one of the alternatives, the key will refer us to a specific number for the next step (or to a named branch); there we repeat the process with a set of new characters. We continue in this way until we arrive at a result - usually the scientific name of the specified species or at least genus or family, often accompanied by a brief description.

At that point, we should verify a particular finding: good quality keys usually contain a more detailed description or illustration of the organism in question, which allows us to confirm a match. It is advisable to compare the specimen identified with descriptions and pictures in the literature or with specimens in collections. The actual identification of the species is not given by the key itself, but only by confirming the characteristic features - the key will give us the most likely answer, which is good to check independently. For example, after identifying a beetle using the key, we can consult a beetle atlas and check whether all the features (colour of the scutellum, shape of the antennae, etc.) match.

It is important to be aware of possible pitfalls during the identification process. If a specimen does not match any of the options in the identification step, it may mean that we have gone down the wrong path in the key (e.g. a feature missed in a previous step) or that our insect is exceptional (e.g. it does not have wings, although most related species do). In such a situation, it is best to take a step back and verify the previous decision, or try an alternative key path. With good quality keys, if we take the wrong branch, we soon run into an apparent inconsistency and can backtrack. Sometimes it also helps to go through both options of a given couplet in parallel - to try one path temporarily and see if it leads us to a logical result; if not, to go back and take the other option. Practice and experience with a given group of insects will teach the user to recognize which characters tend to be variable and can be confusing, and conversely which differences are reliable.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the identification key is a tool that facilitates identification - but it is not a substitute for the critical judgment of an expert. The key helps us to rule out non-matching possibilities (in this it is very effective), but it does not prove with 100% certainty that the determined result is correct. There is always the possibility that the individual under study is not included in the key (e.g. a new or rare species, a different geographical area, etc.). Therefore, after going through the key, we should treat the resulting name as a hypothesis to be confirmed by further study - a standard procedure in professional entomology.

5. Tools needed for determination

Successful insect determination requires not only knowledge, but also appropriate tools. The basic equipment is an optical instrument: either a good quality magnifying glass (for larger specimens) or a binocular microscope. Many small species or subtle features (e.g. wing venation, surface hair, detailed shape of antennae or genitalia) cannot be discerned with the naked eye - here the stereomicroscope is indispensable, as it provides a three-dimensional (stereoscopic) image of the observed object. It is ideal for studying the surface structures of insects (cuticle, pubescence, sculpture, body shape).

Successful insect determination requires not only knowledge, but also appropriate tools. The basic equipment is an optical instrument: either a good quality magnifying glass (for larger specimens) or a binocular microscope. Many small species or subtle features (e.g. wing venation, surface hair, detailed shape of antennae or genitalia) cannot be discerned with the naked eye - here the stereomicroscope is indispensable, as it provides a three-dimensional (stereoscopic) image of the observed object. It is ideal for studying the surface structures of insects (cuticle, pubescence, sculpture, body shape).

When selecting a microscope, I recommend looking at the following parameters:

- the overall rigidity of the structure (holder, stand or arm, which ensures accuracy and the possibility of gentle movement)

- basic optical magnification (must be able to see fine features such as striations, projections or bristles; select stereo microscopes with magnification of at least ≧ 90×)

- the choice of magnification (fixed vs. zoom: each has its advantages and disadvantages, I prefer zoom for convenience in microscopes)

- the minimum distance of the objective lens from the object to be observed (this determines the possible working space; when using the microscope also for preparation it is at least 80 mm)

- illumination (important when observing details; I recommend LED lighting from above (reflective) or ring lighting around the objective)

- options for accessories (eyepieces, objectives, filters, eyepieces)

- quality of optics (lower quality means distortion, chromatic defects)

- photographic recording possibilities (e.g. third tube)

Tools for handling specimens are also needed: most often entomological tweezers to hold and carry insects and entomological needles or pins to attach small parts. For field and laboratory work, plastic or glass dishes (e.g. petri dishes) are useful for orientation sorting of insects. Of course, good lighting is essential - both the stage magnifier and the microscope often have a built-in lamp; alternatively, a headlamp or directional lamp can be used so that the characters can be seen clearly from all angles.

Of course, the identification keys themselves are an essential aid - i.e. specialist books or electronic applications. In addition to the keys, atlases and picture guides are also used to supplement the determination with photographs for checking. For more demanding determinations (e.g. of small insects), other laboratory tools such as a preparation kit (scalpel, fine scissors, preparation needles) may also be useful to reveal important characters - for example, genitalia are often prepared in beetles. However, these advanced methods require experience. A keen eye equipped with a magnifying glass, a good wrench and patience are sufficient for most common insect identification.

Modern faunistics and systematics require a high level of documentation. Calibration slides (micrometric scales) or eyepieces with built-in scales for precise measurements under a microscope are useful for calculating various morphometric indices. Magnifying equipment for photography(macrophotography) is also practical to capture details and consult with other experts when necessary.

6. The most common errors in determination

Even experienced entomologists sometimes make mistakes when making determinations. The most common mistakes include incorrect key work - either too meticulous or, on the contrary, careless. The first type of error consists in the determiner adhering too strictly to every word of the key and falling into cluelessness at the slightest deviation. It must be remembered that organisms are variable and the descriptions in the key represent ideal simplified characters. Individual specimens may vary slightly from the "textbook" description - therefore, the specimen may not fit the exact wording in the key. If we hit a step where we cannot clearly decide between two options, we must not give up immediately. We should first consider whether our specimen really does not fit either option, or whether we just don't have enough experience to recognize the trait. For example, the two alternatives may describe differences in wings, but our specimen has no wings - in which case we are probably lost in the winged insect section of the key, or we are holding an exceptional wingless specimen that is not accounted for in the key. If, on the other hand, both possibilities apply, we can try a trial run of one of them and see if the next steps lead us to a reasonable result; then go back and try the other branch. In the right key, it usually soon becomes apparent which is the right path, because the characters soon begin to clearly disagree on one of them. The important thing is to remain calm and think logically - this patience and confidence in one's own judgement is gained through practice.

The most serious error in entomology, which distinguishes amateur work from serious systematic work, is the attempt to make a species determination without carrying out the necessary specialized preparation. In many families of beetles, accurate species identification is impossible without preparation and microscopic study of the chitinized parts of the genitalia. Ignoring this step leads to a high probability of misidentification.

Another common error is, on the other hand, overconfidence in the key and hasty closure of the case. Someone runs the key quickly, "runs out" the resulting species, and without further verification, labels the specimen and places it in the collection. This approach can lead to mistakes - especially in difficult groups where only a few characters are distinguished in the key and these may be variable. It is then the case that misidentified species are erroneously published, causing confusion in the literature. It is important to note that the identification key itself does not guarantee 100% accuracy. Key authors usually include known species from a particular area, but it may be that your specimen belongs to a species that is not in the key (e.g., a species introduced outside its usual range, or a new species not scientifically described). Thus, the key suggests "it could be XY", but the correct procedure is to then critically compare the determination with other sources. Ideally, one should find a detailed description of the species in a monograph or on a reliable website and verify all the characters, or consult the determination with another expert.

Other mistakes occur if the wrong key is used - for example, a key from a different geographical area where a different species composition occurs. In this case, the key may lead us to the nearest similar species, which may not inhabit our area. It is therefore advisable to choose keys for a given region (e.g. Central Europe). Similarly, it is inappropriate to try to identify e.g. a larva using an adult key - the developmental stages of insects often look quite different and require special keys. It is also a mistake to overlook the explanations and technical terms given in the introduction of the key. Good quality keys include a glossary of morphological terms and abbreviations - it is essential to become familiar with these, otherwise we may misinterpret a character. For example, terms such as hip vs. hip or shield vs. shield may be confusing to the layman, who might choose the wrong branch of the key. It is also a mistake to rush - determining requires concentration; if you are unsure, it is better to think about the step longer or take a magnifying glass or ruler and measure or examine the sign again. Every entomologist learns over time that mistakes in determination are part of the learning process - the important thing is to learn from them and proceed more carefully next time.

7. Recommended keys for Central European Coleoptera

For the Central European coleopterologist, it is essential to rely on a combination of historically proven, comprehensive works and modern, specialized monographs that integrate new methodological knowledge. Links to many of these can be found in Information Resources -> Library.

- Die Käfer Mitteleuropas (Freude, Harde, Lohse). It is considered an essential part of the library of every serious coleopterologist.

- Key to the Animals of the Czechoslovakia (ed. Kratochvíl J.): A historically significant publication that laid the foundation for generations of Czech and Slovak entomologists. Although it is older, some parts of it are still a valuable source of information.

- Vladimír Javorek (1947): Key to the Determination of the Beetles of Czechoslovakia - A classic monumental work (almost 1000 pages) containing keys to the families, genera and species of about 1500 of the more "common" species of beetles of Czechoslovakia. The book also includes an introduction to beetle morphology and a guide for collectors. Although the nomenclature of species is now obsolete, Javork's key still provides a valuable basis for orientation in beetles.

- Karel Hůrka (1996). The publication has 565 pages and contains numerous illustrations and descriptions of characters.

- Stanislav Laibner (2000). Contains identification keys for 177 species and subspecies occurring in our region, supplemented by notes on morphology, distribution and bionomics of adults and larvae. The publication (292 pages) is bilingual and published by Kabourek.

- Leo Heyrovsky (1955) & Stanislav Sláma (supplement 1982): keys to carpenter beetles (Cerambycidae) - The classic identification key to carpenter beetles by L. Heyrovsky (published in the 1940s-1950s), expanded and updated with a supplement by S. Sláma. It provides a detailed identification key to all genera and many species of Central European carpenter beetles. Although more modern works exist today, Heyrovsky's key is the historical basis for this family.

- Ivo Jeniš (2001): Carpenters of Europe I (Vesperidae & Cerambycidae) - The first volume of a pictorial atlas and key to the carpenters of Europe, focusing on the families Vesperidae and Cerambycidae. It includes colour

photographs and distribution maps, together with identification characters for genera and species (text in both English and Czech). A useful resource especially for comparison of species occurring also in Central Europe. - Karel Hůrka (2017): Beetles of the Czech and Slovak Republics - An illustrated publication that is not a classic key, but offers colour photographs of more than 1,000 species of our beetles from all 105 families. For each family, a representative species is listed with a description of its ecology. This book serves as a great supplement to identification keys - allowing quick verification of the species being identified by appearance.

In addition to the resources listed, there are a number of other specialized keys on subgroups of beetles that have been published in journals or independently (e.g., Academia Publishing). For reliable determination of taxonomically difficult groups, it is crucial to use up-to-date, specialized monographs. These publications implement modern preparation procedures and use characters that were previously unavailable. Modern keys integrate data beyond mere morphology. Determination is supported by descriptions of ecological requirements, diet analyses, and accurate distribution maps for each species. This additional information serves as an important confirmatory feature in verifying the determination.

Comparative series

A comparative series is a set of multiple specimens (individuals) of a species arranged for the purpose of comparing morphological characters. Thus, it serves as a visual and practical aid to compare individuals with each other and to evaluate their characters. The use of comparison series (comparative series) in the determination of beetles (Coleoptera) is very useful in entomology and has a number of advantages. These include:

- More accurate determination of species

A comparative series allows comparison of multiple specimens of the same species and related species. Thanks to this, it is possible to- recognise interspecific differences (e.g. between very similar species),

- distinguish variation within a species (sexual dimorphism, seasonal or geographical variation),

- reduce the risk of misidentification caused by unusual characters in one specimen.

- Study of morphological variation

Comparative series show the extent of natural morphological variation - for example, in the colour of the scruff, the shape of the shield, the size of the body or the structure of the antennae. This makes it possible to determine whether the difference is the result of natural variation or a true diagnostic trait. - Effective training and improvement of determination skills

For both beginning and advanced entomologists, working with a comparative series is an excellent learning tool- it helps to remember the typical characters of each species,

- it allows to perceive subtle morphological differences,

- reinforces the "determinator instinct" and the experience of species variation.

- Verification of the reliability of the determinants

By comparing multiple specimens, it is possible to evaluate which characters are consistent and diagnostically reliable, and which, on the other hand, are subject to variation. This is crucial in the development of identification keys and revisions of taxonomic groups. - Basis for taxonomic and biogeographic studies

Comparative series allow us to observe- geographical variation (e.g. whether populations differ by region),

- evolutionary relationships between related species,

- possible cryptic species that would not be recognised without wider comparisons.

- Validation of controversial cases

In case of doubt (e.g. atypical specimens, damaged individuals or species with overlapping characters), the comparison series (ideally deposited in public collections) serve as the final reference point.

Determination labels

Determination labels (sometimes also determination labels, ID labels) are one of the key components of entomological collections. They serve to document the final determination (identification) of the taxon (species, subspecies) of a given specimen. Their importance and standards of use are essential for the collection to be of scientific value and for the correct interpretation of older materials.

The identification label serves several key functions:

- Taxon identification: Provides the exact scientific name of the designated species (and subspecies, if applicable).

- Scientific value: confirms that the individual has been identified. Together with the locality label (which indicates the location and date of collection), it forms a complete documentation that allows the specimen to be used for faunistic, taxonomic, or ecological research (e.g., mapping the distribution of a species over time and space).

- Taxonomic tracking: gives the name of the author of the determination and the year in which the determination was made. This is important because scientific names can change over time (revisions, new nomenclature). Thus, the entomologist always knows who made the determination and when.

- Type material: for type specimens (holotypes, paratypes, etc.) that bear a scientific name, the label is crucial for their unmistakable identification. Type labels are often conspicuous (e.g. red) and contain specific information.

- Verifiability: any specialist can verify the determination and, if necessary, add a new, corrected determination to the label.

Entomological collections have strict and internationally recognized standards for writing, formatting, and placement of labels to ensure clarity and durability of information.

Standards for the use of deterministic labels

- Determination label content

A determination label should contain at least the following information- The scientific name of the taxon

- Genus, species (and subspecies if applicable).

- Name of the author who described the taxon and year of description (e.g. Carabus variolosus Fabricius, 1787),

- if relevant, form of uncertainty designation (e.g., "cf.", "aff.", "?").

- Author's determination

- The name (often abbreviated) or initials of the person who determined the individual (e.g., Det. J. Novak, Rev. J. Novak). The abbreviation det. means determinavit (determined), the abbreviation rev. means revisus (revised).

- Year of determination

- The year in which the determination took place (e.g. 2023).

- The scientific name of the taxon

- Format and material

- Material. For type specimens, coloured paper is often used (e.g. red for the holotype).

- Lettering: The lettering must be permanent and indelible. In the past, ink writing was used, but today printing in very small and sharp type is most often used.

- Size: The labels are deliberately very small (typically 10 x 5 mm to 20 x 8 mm) so that they are not obstructive under the specimen but are legible.

- Label placement

Labels are placed on a pin under the insect, underneath in a precise order- Top: Location/Locality label: collection details (state, locality, date, collector). This label is primary and most important for the scientific value of the specimen.

- Middle: Determination label: determination data (see above).

- Bottom (if needed): Additional labels (e.g., ecological notes, DNA extraction, type label - this is usually placed just below the insect or in another visible position and is usually colored).

Important rule: If a determination is later corrected or revised, the original determination label is never removed. The new label is placed underneath, allowing the taxonomic history and determination of the specimen to be tracked.

The organization of the collection

Proper collection organization ensures that the collection has scientific value, long-term durability, and ease of orientation.

The organization of an entomological collection is based on three basic goals - to ensure the clarity and accessibility of the collection, to protect the specimens, and to ensure the documentary value of the collection.

- Clarity and accessibility - to be able to find specimens quickly by systematics, locality or other criteria of collection organization.

- Preservation of materials - both physical and chemical - so that specimens will last for decades to hundreds of years.

- Documentary value - each specimen must be uniquely associated with provenance and identification data (kept in a logbook, card catalogue, database).

Basic arrangement of the entomological collection

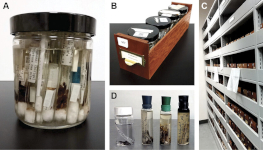

Insects are stored in special lockable boxes (museums) or cabinets to protect them from light, dust and pests (such as piscivores or disturbers).

- Systematic (taxonomic) sorting is by far the most common way of arranging a collection and is used in museums and research collections. The ordering is thus organized according to a taxonomic hierarchy: order ⟶ family ⟶ genus ⟶ species/subspecies. Within each taxonomic group (e.g. family), an alphabetical ordering of genera/species according to Latin names is then often used. This sorting method facilitates comparison, identification and access to taxonomic references and is used by all major national museums.

- Another option is geographical (biogeographical) ordering, i.e. ordering by collection area (continent, country, region, locality). This type of ordering can be useful for faunal studies, biogeography or ecological purposes. The disadvantage is that taxonomic relationships of specimens are not in close proximity, making it more difficult to compare related taxa from different areas. In practice, geographic collections are often combined with systematic layering (i.e. within the geographic module the arrangement is taxonomic). Reference/regional collections often resort to this type of classification for easy access to local species.

- Other ways of ordering specimens within a collection tend to be exceptional and are usually charged with the narrowly focused purpose of building that collection. They tend to be inappropriate for building an amateur collection, so we will not deal with them further.

Physical organization of specimens in the collection

- Storage of specimens

- Pinning: larger species are impaled on entomological pins (most commonly size 2 - 3).

- Labelling: small beetles are glued onto rectangular, triangular or pentagonal labels attached to the pin.

- Storage in wet collections: soft-bodied species (e.g. larvae) are stored in 70 - 96% ethanol or 4% formaldehyde.

- Drawers and boxes

- Entomological drawers (as part of entomological cabinets) or entomological boxes with sealed lids and soft liners (polystyrene, porous, ...) are used.

- Each drawer or box is marked with a systematic name and number.

- Drawers and boxes shall be stored in air-conditioned rooms with low humidity.

- Labelling

Each specimen usually has- Location label - place, date and collector (e.g. "Czech Republic, Krkonoše Mountains, 15.6.2024, leg. J. Novák").

- Determination label - species identification, name of the determiner, year (e.g. "Carabus coriaceus L., det. P. Černý, 2023").

- Supplementary labels - e.g. about revision, DNA sample, type ('paratypus', 'lectotypus').